Post by Magnet Man on Jan 30, 2008 18:47:54 GMT -5

My father was thirty three years old when he was killed in a construction accident. The tragedy happened less than five years after he returned from WWII. He was neither high-born or a public personage, or a recognized war hero, yet many thousands of people, from all walks of life and from all along the length and breadth of the Witwatersrand, attended his funeral. The massive turn-out was entirely unexpected, so no one thought to count the actual numbers of mourners, It was estimated by some that there was somewhere between three and five thousand people - and therein lies an untold Imperial tale.

The day of my father’s funeral remains clearly etched in my memory. I was nine years old when he died. He was buried in Boksburg cemetery, just a few paces from the grave of his parents. Grandma has just died the year before and the family had her body interred in the same grave as grandpa, right on top of him. That fact always got to me when we visited the graveside. The family saga of how and why a fourth generation English colonial and Afrikaans meisie crossed the forbidden ethnic zone and got themselves hitched right in the middle of the Anglo/Boer War, is another odd untold Imperial tale. Since all who knew the intimate details are long dead that turn of the century love story will probably never be told. What I do know is that grandma never spoke one single word about the Boer side of her family. Nobody on our English side ever met any of them. She had been completely ostracized for marrying the enemy and rearing English-speaking children. My father, half English, half Dutch, was their tenth born.

I remember the slow drive behind the hearse that carried my dad’s disfigured body out to the cemetery after the Church service. The accident that killed him had been gruesome. While building a steel bridge over the Vaal River, a five ton steel girder had slipped its cable sling. It was kept aloft at the other end by the second sling. It leaned against the side of the bridge at a precarious angle, some forty feet above the ground. My dad climbed up in an attempt to rescue the valuable beam before it fell into the river. While trying to secure it, the giant girder suddenly slid towards him. It sheared off his right arm at the shoulder and swept him back along the bridge to the ground. The head-first fall killed him.

Mourner’s cars were parked in the dirt on both sides of the Main Reef road all the way from the edge of town to the graveyard, and continued on for another mile beyond. Throngs of people who had to leave their cars were walking to the cemetery. They left just enough room for the funeral procession to pass though. Mom’s face was hidden behind a black veil and I could not see her expression. My younger brother and sister sat silently and solemnly beside her. I was in the front seat, beside my uncle who was driving my dad’s new black Chevrolet that he had bought only months previously.

A silent crowd was densely packed around the open grave when we got there. The tears started later, when the coffin was slowly lowered into the ground. Where ever I looked people were crying. Mom, uncles, aunts, strangers, both male and female; my younger brother was beside himself and had to be restrained from jumping into the grave. Amongst that sad multitude it seemed that I, the elder son, was the only one left tearless.

Questioning my lack of emotion beside my dad’s grave was a signal moment for me. I guess that is when I began my life-long philosophical apprenticeship as a social analyst. Before then I had only experienced sporadic bursts of personal and social inquiry. The first was when I was four and half. That was the day my dad came home from the war. That was another moment which remains clearly etched in my memory, and from which I gleaned private insights into infant psychology. My brother, thirteen months younger and not yet fully weaned, bonded instantly and naturally with my dad - right from the first moment he saw him. I could not do it. Later I was able to connect my intuitive understanding of the difference between our reactions to scientific evidence, which revealed that the neural pathways between the intuitive and analytical halves of his infant brain had not yet matured. In effect, there was no sense of critical separation between him and the world – thus his acceptance of his dad was unquestioning. My father came home a year too late for me. The neural connections were already made. I was a separate observing self that questioned my relationship to all else. I realized that he was my father – but a child is not generally supposed to find itself analyzing that un-natural fact at so young an age – a fate suffered, I suppose, by tens of thousands of war babies, throughout historical time. Over the remaining years of his life I learned to admire and respect him and feel proud that he was my dad, but the father/son bond intended by Mother Nature never truly happened. So Dudley suffered when he died and I stood unmoved, wondering about the emotional outpouring that surrounded me. Why were so many thousands of strangers present at this common man’s funeral? Why such a universal out-pouring of grief? Surely so many thousands could not have all known my father personally? It took me years to puzzle the whole thing out.

Boksburg was our family’s hometown. Grandpa presided in court as Boksburg’s magistrate. He fathered a large family. His twelve children were born and raised in the town and attended the local schools. During his later teens my dad added luster to the family name by becoming the reigning Provincial light-weight amateur boxing champion. Those facts would have accounted for a reasonably decent turn-out at his funeral – a hundred people perhaps, not thousands. He had left school at fourteen and served the years before the war interrupted as an apprentice engineer on the gold mines. The giant shafts along the East Rand and West Rand reefs are the largest gold mines on the planet. My father was one of the tens of thousands of miners who worked the reef. His seven years on the mines would have accounted for a lot of fellow workers at his funeral, but the numbers were still far too high. Frequent fatalities under-ground, usually had multiple deaths. Fires were sparked by the accidental ignition of invisible methane gases. Deep-level pressure bursts killed a dozen or more men at a time. Hundreds of individuals died yearly from miner’s phthisis – their lungs turned solid after years of breathing in rock dust. But no mine funeral of any magnitude on record had ever attracted such a great crowd.

I concluded that the final piece of the puzzle had to lie in his war record. Though no more decorated than the average soldier, some aspect of his service in WWII had to hold the answer. Dad never spoke about his time in the war. When I got older I did my own research.

By 1940 it was obvious that Great Britain could not defeat the Germans without help. With the United States hanging back, England called for more soldiers from each of the colonies of Her Empire. South Africa, as a standing member of the Common Wealth, enjoying all its trade preferences and military protection, together with Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and the rest of the South East Asian colonies, complied with the Imperial call up. Our country sent twenty fully armed regiments into the war. My dad was assigned to the South African Engineering Regiment and left for the front in 1941, three months after I was born. Over the next four years he served under Montgomery in North Africa and took part in of the invasion of Italy. He ended the war as regimental sergeant major. The fact that he was the top NCO in his regiment, responsible in large part for the lives of five thousand other engineers, most of them from the Witwatersrand, made me think for a while that here might be the answer to the huge turn-out. But again, that did not add up. No single soldier could have become that revered. It was only many years later that the true answer finally dawned on me.

As the first young soldier of note to die so soon and so tragically after the war, my father’s death was symbolic. Of the one hundred thousand troops that South Africa sent to the front, ten thousand nine hundred soldiers never returned. The majority of them were from the Witwatersrand. None of their bodies came home. All were buried abroad in the massive military cemeteries dotted all over Europe. No relatives had been at their grave-sides to mourn their passing. All of that national loss and grief had been bottled up for years. With my father’s untimely death, grieving families had an actual soldier’s body to bury. Several thousand families had come to my father’s funeral, not simply to pay their respects to his passing, but to mourn the death of their own loved ones who had died in a distant war. By attending, it offered a chance to let it all the tears flow out. And that, I believe, is why so many thousands of mourners attended the funeral of an Imperial soldier.

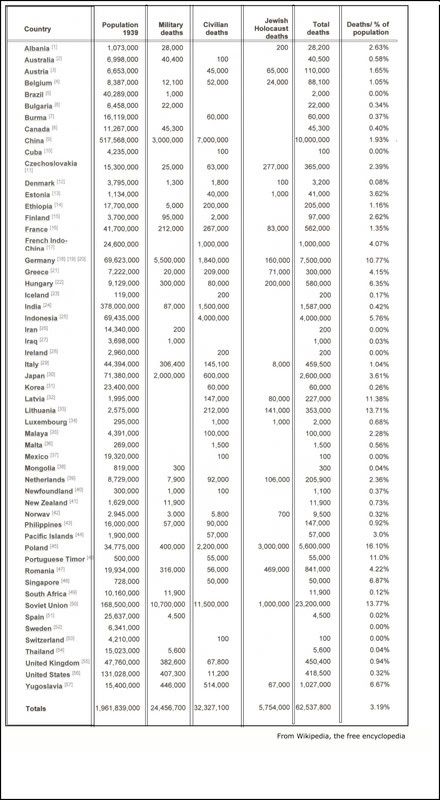

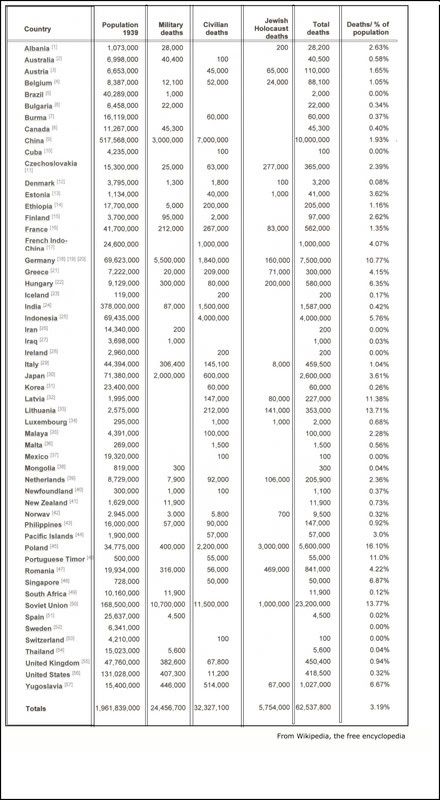

I have always wondered how other members of the British Empire coped with their war grief.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_War_II_casualties

The day of my father’s funeral remains clearly etched in my memory. I was nine years old when he died. He was buried in Boksburg cemetery, just a few paces from the grave of his parents. Grandma has just died the year before and the family had her body interred in the same grave as grandpa, right on top of him. That fact always got to me when we visited the graveside. The family saga of how and why a fourth generation English colonial and Afrikaans meisie crossed the forbidden ethnic zone and got themselves hitched right in the middle of the Anglo/Boer War, is another odd untold Imperial tale. Since all who knew the intimate details are long dead that turn of the century love story will probably never be told. What I do know is that grandma never spoke one single word about the Boer side of her family. Nobody on our English side ever met any of them. She had been completely ostracized for marrying the enemy and rearing English-speaking children. My father, half English, half Dutch, was their tenth born.

I remember the slow drive behind the hearse that carried my dad’s disfigured body out to the cemetery after the Church service. The accident that killed him had been gruesome. While building a steel bridge over the Vaal River, a five ton steel girder had slipped its cable sling. It was kept aloft at the other end by the second sling. It leaned against the side of the bridge at a precarious angle, some forty feet above the ground. My dad climbed up in an attempt to rescue the valuable beam before it fell into the river. While trying to secure it, the giant girder suddenly slid towards him. It sheared off his right arm at the shoulder and swept him back along the bridge to the ground. The head-first fall killed him.

Mourner’s cars were parked in the dirt on both sides of the Main Reef road all the way from the edge of town to the graveyard, and continued on for another mile beyond. Throngs of people who had to leave their cars were walking to the cemetery. They left just enough room for the funeral procession to pass though. Mom’s face was hidden behind a black veil and I could not see her expression. My younger brother and sister sat silently and solemnly beside her. I was in the front seat, beside my uncle who was driving my dad’s new black Chevrolet that he had bought only months previously.

A silent crowd was densely packed around the open grave when we got there. The tears started later, when the coffin was slowly lowered into the ground. Where ever I looked people were crying. Mom, uncles, aunts, strangers, both male and female; my younger brother was beside himself and had to be restrained from jumping into the grave. Amongst that sad multitude it seemed that I, the elder son, was the only one left tearless.

Questioning my lack of emotion beside my dad’s grave was a signal moment for me. I guess that is when I began my life-long philosophical apprenticeship as a social analyst. Before then I had only experienced sporadic bursts of personal and social inquiry. The first was when I was four and half. That was the day my dad came home from the war. That was another moment which remains clearly etched in my memory, and from which I gleaned private insights into infant psychology. My brother, thirteen months younger and not yet fully weaned, bonded instantly and naturally with my dad - right from the first moment he saw him. I could not do it. Later I was able to connect my intuitive understanding of the difference between our reactions to scientific evidence, which revealed that the neural pathways between the intuitive and analytical halves of his infant brain had not yet matured. In effect, there was no sense of critical separation between him and the world – thus his acceptance of his dad was unquestioning. My father came home a year too late for me. The neural connections were already made. I was a separate observing self that questioned my relationship to all else. I realized that he was my father – but a child is not generally supposed to find itself analyzing that un-natural fact at so young an age – a fate suffered, I suppose, by tens of thousands of war babies, throughout historical time. Over the remaining years of his life I learned to admire and respect him and feel proud that he was my dad, but the father/son bond intended by Mother Nature never truly happened. So Dudley suffered when he died and I stood unmoved, wondering about the emotional outpouring that surrounded me. Why were so many thousands of strangers present at this common man’s funeral? Why such a universal out-pouring of grief? Surely so many thousands could not have all known my father personally? It took me years to puzzle the whole thing out.

Boksburg was our family’s hometown. Grandpa presided in court as Boksburg’s magistrate. He fathered a large family. His twelve children were born and raised in the town and attended the local schools. During his later teens my dad added luster to the family name by becoming the reigning Provincial light-weight amateur boxing champion. Those facts would have accounted for a reasonably decent turn-out at his funeral – a hundred people perhaps, not thousands. He had left school at fourteen and served the years before the war interrupted as an apprentice engineer on the gold mines. The giant shafts along the East Rand and West Rand reefs are the largest gold mines on the planet. My father was one of the tens of thousands of miners who worked the reef. His seven years on the mines would have accounted for a lot of fellow workers at his funeral, but the numbers were still far too high. Frequent fatalities under-ground, usually had multiple deaths. Fires were sparked by the accidental ignition of invisible methane gases. Deep-level pressure bursts killed a dozen or more men at a time. Hundreds of individuals died yearly from miner’s phthisis – their lungs turned solid after years of breathing in rock dust. But no mine funeral of any magnitude on record had ever attracted such a great crowd.

I concluded that the final piece of the puzzle had to lie in his war record. Though no more decorated than the average soldier, some aspect of his service in WWII had to hold the answer. Dad never spoke about his time in the war. When I got older I did my own research.

By 1940 it was obvious that Great Britain could not defeat the Germans without help. With the United States hanging back, England called for more soldiers from each of the colonies of Her Empire. South Africa, as a standing member of the Common Wealth, enjoying all its trade preferences and military protection, together with Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and the rest of the South East Asian colonies, complied with the Imperial call up. Our country sent twenty fully armed regiments into the war. My dad was assigned to the South African Engineering Regiment and left for the front in 1941, three months after I was born. Over the next four years he served under Montgomery in North Africa and took part in of the invasion of Italy. He ended the war as regimental sergeant major. The fact that he was the top NCO in his regiment, responsible in large part for the lives of five thousand other engineers, most of them from the Witwatersrand, made me think for a while that here might be the answer to the huge turn-out. But again, that did not add up. No single soldier could have become that revered. It was only many years later that the true answer finally dawned on me.

As the first young soldier of note to die so soon and so tragically after the war, my father’s death was symbolic. Of the one hundred thousand troops that South Africa sent to the front, ten thousand nine hundred soldiers never returned. The majority of them were from the Witwatersrand. None of their bodies came home. All were buried abroad in the massive military cemeteries dotted all over Europe. No relatives had been at their grave-sides to mourn their passing. All of that national loss and grief had been bottled up for years. With my father’s untimely death, grieving families had an actual soldier’s body to bury. Several thousand families had come to my father’s funeral, not simply to pay their respects to his passing, but to mourn the death of their own loved ones who had died in a distant war. By attending, it offered a chance to let it all the tears flow out. And that, I believe, is why so many thousands of mourners attended the funeral of an Imperial soldier.

I have always wondered how other members of the British Empire coped with their war grief.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_War_II_casualties